Thursday, December 30, 2010

See You on the Other Side

So the only reason why I'm doing a "best and worst of" summary of the year's movies is because I'm frankly too slack to go and see The Kids Are All Right and then still write about it.

I started this blog halfway through the year so I don't have to worry about what went before that, but I think The Secret In Their Eyes is the best movie of the year anyway. It had drama, comedy, romance and insight, which is always better than any special effect.

This Argentinean film should have won the Oscar for best film - in any language.

Biting at its heels was a tiny, low-budget film that the New Zealand Film Commission didn't deem good enough to produce, but Rosemary and Mike Riddell's The Insatiable Moon had the same qualities as the aforementioned work and is still proving its worth at that great leveller, the box office.

Though I went a bit overboard with four "excellent"s in my review, a very camp Pacific Islander kind of echoed that when he told a rather stiff Pakeha couple in the queue ahead of him that it was "brilliant".

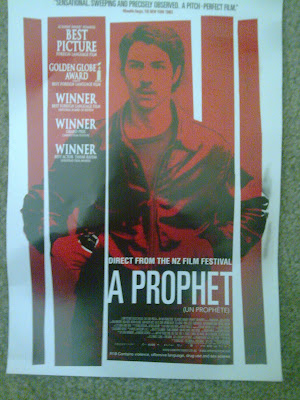

Another great, disturbing and even more contemporary film was A Prophet, giving us a glimpse into how casual but sustained prejudice against Islam merely leads to its increasing radicalisation. Done in that almost blank style of some French movies and maybe a tad too long, its message comes across loudly and clearly.

In fact, it was a very good year for French movies, what with the wonderfully laconic Farewell, starring that great director Emir Kusturica, and the uplifting The Concert deserving all the praise that was lavished upon them. Both their stories had fascinating Russian connections, which made a welcome change from the usual Anglo-American axis.

France-based Roman Polanski also made a welcome return to form with his vicious political satire on that very relationship in The Ghost Writer, starring Ewan McGregor and Pierce Brosnan. It, too, has no special effects but is doing steady business at the box office.

The Social Network is still doing well at the BO, but can anyone remember any kind of story? And does it matter to the Attention Deficit generation? Apparently not. They seem to like their bites short, simultaneous and, uh, well, like, you know...

Lastly, two low-budget dramas that punched way above their weight had this reviewer gaping at their quality of old fashioned storytelling. Winter's Bone is as chilling as its title suggests and has everyone sitting up and taking notice of its director, Debra Granik, and star Jennifer Lawrence.

The Disappearance of Alice Creed is surely the lowest-budget movie of the year, but it's as taut as a crossbow string on either side of the arrow, pointing straight at that little point between your eyes.

There weren't many notable comedies this year, partially because they are so difficult to make and easy to forget because they're usually so bad, but the Coen brothers made a masterpiece in A Serious Man. If it's slightly too Jewish for some people's taste, it's still an ultra-clever bit of fatalism.

Not far behind it was the German comedy Soul Kitchen by Fatih Akin, describing just how resilient and funny the life of a migrant worker can be.

As for dogs of the year, with all respect to canines, The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest must surely rank as the most allergy-inducing study in entitlement of a woman, not a girl, in 2010. Due Date was without a doubt the most over-hyped and under-delivering comedy.

They really strained one's patience, not to mention pocket.

Talking about hype, The King's Speech has got so much of it so long before its release - January 20 - that one wonders whether its trailer is also better than the real thing.

Whatever the case, it stars Colin Firth who has had one hell of a productive period with films like Genova, Dorian Gray and A Single Man, a film that is right up there with the rest of this year's more intelligent fare.

According to an interview seen on TV recently, Firth reckons that if you chant "Oscar" often enough you'll win it, but he should get it as much for his talent as for one of his many self-deprecating quotes. Here's one from the Internet Movie Database:

"People will tell you they act because they want to heal mankind or, you know, explore the nature of the human psyche. Yes, maybe. But basically we [actors] just want to put on a frock and dance."

And now I'm going on holiday to practise my thousand-yard stare for two weeks, so there'll be nothing doing on this blog until I get back.

Happy New Year.

Neil Sonnekus

Thursday, December 23, 2010

A is for Ass-kicking

Two movies in which women aren't support systems for men but getting up to all kinds of trouble of their own, and that during the stupid season.

In the more commercial Easy A, Emma Stone plays "an average school girl" who tells a lie about losing her virginity as a joke and sets off a rumour mill that spirals way out of control. The book she is studying at school happens to be The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne, which exposes Puritanical America's sour little heart to the core.

This film cleverly continues that fine tradition with something most films these days lack: charm.

Stone, of course, does not look or act like an average school girl. She is the all-American redhead - tall, wide mouth, slight lisp, knowing voice over. She could play anything from a slightly older Lolita to a Kathleen Turner who launched a murderer in Body Heat. She is so charged with suburban sexuality that she just has to walk to exude her own erotic subtext.

Secondly, it's a pity that her very hip parents, played very well and wackily by Stanley Tucci and Patricia Clarkson, had to adopt a black child, who doesn't work. He's just there. Then again, the story is generally so clever that this becomes quite a slap in the direction of over-well-meaning liberals.

Neither does Lisa Kudrow exactly convince as a serious school counsellor; we expect her to be wacky and she insists on being seriously neurotic. Or rather, her writer/director Will Gluck does, which is a pity.

But those are side issues: the main thing is that this isn't a comedy that starts off with cheap jokes and ends with a car chase. It's confident enough in itself to let the laughs come filtering through from the halfway mark on, and it takes such a savage swipe at modern fundamentalist Christianity that one wonders whether the suits who green-lighted it actually understood what they were doing.

Maybe the producer told them it was a high-school comedy about how gossip can spiral out of control and showed them the talented Stone's audition reel instead of the script.

At the very other end of the scale financially, and across the Atlantic geographically, is The Disappearance of Alice Creed.

Starring exactly three people - there aren't even extras - it is not boring for one second. Two men kidnap a woman and take her to a flat they have specially furnished for their needs: a soundproof room with a strong, bolted bed and plenty of handcuffs. They've even thought about her toiletry needs.

But slowly some interesting facts start emerging. As with so many crimes, there's a personal element to this one. One of the kidnappers, Danny (Martin Compston), actually knows the rich daddy's girl, Alice (Gemma Arterton).

Loves her, in fact. Or rather, he says so. And when she discovers it's him, she also says so. But Vic (Eddie Marsan) also has some involvement here, and he senses that the weaker Danny is having all kinds of doubts, or maybe he's just acting that way. And then, hello, the two men also have something a little more than just a mutual criminal mission going on between them.

Arterton plays her part to perfection, using the little scope she has to the utmost: her body and her wiles.

If the first 10 minutes are unnecessarily contrived - why don't Danny and Vic talk to each other, and why would there be lighting and working toilets in a very high, unused block of flats? - then we forgive that because this is a low-budget movie that is as much about crime as it is about sexual politics.

Every film student who is serious about making a break into the industry should watch this flick to see just how three people in a couple of locations can have you squirming in your seat, wondering what the hell is going to happen next.

Neil Sonnekus

Thursday, December 16, 2010

The Bones of Hollowood

In the case of her latest film, unfortunately, there is very little to praise. In fact, the very first image of Somewhere pretty much sums up 90% of the movie: a black Ferrari speeds round and round a dirt track, the camera perfectly still and letting the car roar in and out of frame. This happens about five times and there are no credits, just the monotonous sound of the car and a view of the desert outside Los Angeles.

Then Johnny Marco (Stephen Dorff) gets out of his car and we can see that he's no flashy dresser. In fact, he's going to wear the same old boots, jeans and various check shirts throughout this film. Unlike the kind of actor who has come up through the ranks of college and theatre productions, he was clearly one of those good-luck stories of going to a film audition for a laugh, getting the part and becoming spectacularly rich and famous.

When an actor asks him about Method acting at one of those interminable La La Land parties, Johnny can scarcely answer him, except to say something like hang in there. Women throw themselves at him but he is so bored that he falls asleep with his head between a woman's thighs.

If there are such moments of droll humour, they are very few and far between. A lot of the film is made up of Johnny sitting on the couch in his famous artist's hotel and smoking. And drinking a beer. And lighting another cigarette.

Or his head is covered in latex for a special effect. He sits on a chair, with only his nostrils showing, and the camera slowly, ever so slowly, tracks in on his monstrous white face while he breathes. The whole idea is that when he sees the final result, himself as an ugly old man, it will spark an existential crisis, but just how laboured does it have to be?

What might have saved him is his lovely daughter, played by the delightfully natural Elle Fanning, who is only tagged along when he is more or less given no other choice but to comply. And when he does half-heartedly apologise to her about maybe not being the most responsible kind of father around, his voice is drowned out by the publicity helicopter droning behind him.

On and on it goes, until he finally realises that his life is - hello - empty.

Coppola seems to be making an homage to her father and especially his Italian contemporaries' existential movies of the Seventies. The only problem is they did it much better and that was then, this is now and the rich still have to earn our sympathy - just as it ever was.

At the very other end of the scale in every respect is Winter's Bone, also by a woman director, Debra Granik.

Unlike Johnny Marco, Ree Dolly (Jennifer Lawrence) does not have the luxury of money or time. Her father is a drug dealer who had been caught and posted his house as collateral to get him out on bail. Now he's disappeared and if Ree can't find him she and her mother and two younger siblings are out on the bones of their arses in a week's time.

The mother has retreated into herself or maybe her brains are just fried by the kind of stuff her husband cooks, so it's all down to 17-year-old Ree.

The setting is the grim Ozark mountain region of southern Missouri and always in the wintry background guns are being fired. They could be hunters' rifles, or they could be drug deals gone wrong. If the mountains are beautiful then people's yards are full of broken caravans and disused tyres.

Usually a film about something that is off-screen doesn't work; here it works a treat, just adding to the menace and uncertainty of Ree's predicament. We actually want to see the father and have him held to account.

But no one will tell Ree where her father is and Granik manages to persuade us that as mean and nasty as these Deliverance-type folks are, the women as much as the men, there is also something innately decent about them.

It's a paradox that is beautifully exemplified by Ree's uncle, Teardrop (John Hawkes), a nasty piece of work on the edge of excessive violence and genuine pity. When she tells him that she's never really trusted him he replies that's because she's a smart girl.

At one stage she is so desperate that she decides to join the army for the $40 000 inducement, but she's too young and the recruiting officer gives her some surprisingly good advice. So not even that ironic course of action will provide a way out.

And so there's the heavy metal music in the background, the forest settings of slasher movies as well as their implements: axes and an electric saw. But it is the realism of the story that makes this film and its final discovery so chilling, even if the ending is a little drawn out.

Winter's Bone didn't win the Sundance Film Festival Prize for nothing, and it and Lawrence have also been nominated for Golden Globe Awards. Somewhere hasn't and probably won't and definitely shouldn't.

But there you have it. Those who are rich and bored out of their minds, and those who will become cannon fodder to help their dependants. Hollywood and America. You either love it or you hate it.

Neil Sonnekus

*Matter of Fact: In my review of Due Date I neglected to mention that the first name of that fine actor Downey Jr is, in fact, Robert. And in last week's review of the dire The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest I inferred that the capital of Sweden is Oslo, which of course it's not. It is Stockholm.

Thursday, December 9, 2010

The Girl With the Attitude Problem

Sweden. - Julian Assange is being accused of sexual molestation in that country and "hacktivists" are trying to paralyse the likes of Mastercard and Visa for withdrawing support from his WikiLeaks.

More importantly, however, hacker and sexual victim Lisbeth Salander (Noomi Rapace) is fighting for her life after surviving a night underground with a bullet in her head, among others.

The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest is the final episode of the Millennium trilogy, based on the late Stieg Larsson's airport thrillers which, in cinematic terms, started off well and, like most sequels, deteriorated rapidly. Here we are scraping the bottom of the barrel beneath the icy, dirty waters of Oslo.

Lisbeth is going to spend much of the movie recovering in hospital, where she responds blankly to the kind of doctor who comes around once in a, well, millennium. Played by I don't know who because the Internet Movie Database doesn't provide a photograph or his title as a clue, all I know is he's one of those kind, level-headed European doctors who will not get even the slightest glimpse of gratitude from madam, who has rapidly used up all of her sympathy quota.

Meanwhile, a lot of old men with Nazi links have endless meetings about how she must be stopped and re-committed to the loony bin, where she was clearly abused by another doctor, another old man.

And then there is the ever-persistent journalist Michael Nyqvist (Mikhael Blomkvist) and his editor and on/off partner Erika Berger (the beautiful Lena Endre), working tirelessly for Lisbeth via his ego.

Yes, there is a lot of atmosphere in the film. We constantly wonder when Lisbeth, Erika, Michael or his pregnant sister, another nameless wonder for the same above reasons, are going to be taken out by some awful Eastern Europeans on those grim, wintry streets.

There is exactly one action sequence and that's when one of the latter almost succeeds in killing Michael in a restaurant. But that, apart from Lisbeth's surly giant of a half-brother who goes around psychopathing everyone, is about it.

The whole thing is going to build towards a court case in which all the old fogeys are relying on the fact that, up to now, Lisbeth has refused to open her mouth in her own defence. And guess what she's going to do in court? Why, she's going to open it, and she's going to show us just how good she is at semantics.

Most absurd of all is that Michael's sister is going to defend Lisbeth. Maybe they don't have conflict-of-interest practices in Sweden, but I very much doubt it. Still, it's very nice seeing Michael looking upon Lisbeth altruistically in the dock in her full black punk regalia, having provided his sister with most of the information they need, and she about to pop a baby just to give it all that extra frisson.

Obviously they win - but does Lisbeth look relieved, happy, grateful? not on your nelly - and by now we are way past the two-hour mark and my Hitchcockian bladder is bursting and I actually have to get to work of the paying variety, but Lisbeth has one more thing to do.

She has to go to a remote barn in the country where her half-brother is hiding out and he, well, I suppose he tosses her about for the benefit of those who like that sort of thing until he ends up hanging from that hook we're shown as she enters, but I can't be sure because by then I'd left for the above reasons and because this franchise was now ready for what Rowan Atkinson calls glorious television.

Thursday, December 2, 2010

Slashing Those Poppies

Murray's obsession with bureaucratic form (roll calls for three), Jemaine's compressed yesses ("Yis") and Bret's inability to express his innate decency, except perhaps through song, seem to be Kiwi to the core. These three lovable miseries are not just characters but also national characteristics, which includes that obsession with our bigger, louder neighbour.

By the same token, the reason why Once Were Warriors was such a success was because it was as primal as, well, a haka. If it dealt with the universal theme of male abuse in the family, then it did so from an unashamedly Maori perspective. There was no liberal, politically correct white pussyfooting; it was the real thing, and it worked, it sold. It was also just one story.

The Insatiable Moon is another film that will transcend its own boundaries, in the sense that I could watch it as a South African and see it deal with a subject echoing that country's Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings in a way that is pertinent, witty and wise.

None of the above films or TV series has an overseas actor in a leading role, which is amazing.

But now we get to films like Matariki by Michael Bennett and Predicament by Jason Stutter. The former, made very much in the ensemble style of Short Cuts and Crash (the Oscar winner, not the more interesting Cronenburg one) in which various people's lives intersect, is set in South Auckland and features the lives and loves of quite a few people. Too many, in fact.

First, there is a pair of teenagers who have the kind of cringe-worthy dialogue of which Jemaine and Bret are acutely aware, some of it giving the impression that it's meant to shock more than necessarily be realistic or logical, let alone funny. This doesn't mean they aren't charming - they are -but we never really get to know why, for example, the Chinese girl doesn't like home: she just stays away.

Then there is Sara Wiseman playing a cop whose Maori husband spends most of his screen time in a coma. What is this very capable and watchable actress expected to do? Emote, and she does it very well, but who is she? All we can deduce is that she wants to be alone with her husband, which is understandable, to the exclusion of his family, which is problematic. She doesn't seem to be on bad terms with them, but that's about all we're going to learn about her.

Likewise, there's a young woman who looks about 11 months pregnant, but when the child does finally come the boyfriend skedaddles and she's not really interested in baba either. Why? Because her junkie man has left her? In the end she leaves both of them, but exactly what her motivations are is not entirely clear.

Matariki is not a "bad" film by any stretch of the imagination: the way a baby stirs a protective instinct in a gay man and how that white baby inveigles its way into a loving Maori family (another positive) that has to make the unenviable decision of turning off someone's life-support system, is profoundly moving.

But the film is trying to keep so many other balls in the air - of which I've only mentioned a few - that it cannot focus on and therefore thoroughly explore this one primal event.

In Predicament there is a man who has the wonderfully weird obsession of building a wooden tower in his back yard to the exclusion of everything and everyone else. His story arc ends (and I don't care what happened in the book) with him starting to talk to everyone around him again, and destroying his dream, his tall, hallucinogenic...poppy.

The film flopped at the box office.

Similarly, in Matariki there is a funky, catchy song called Look What Love Can Do. But it's featured smack bang in the middle of the movie, in a daytime market scene of a mostly night-time movie, and then again over the end titles.

Wrong.

The other thing it doesn't do is let rip, in a Jennifer Hudson kind of way. It really is a spill-your-guts kind of dance-floor number, which could have been a national hit. Did it ever make it to the radio? Did anyone ever push it that way or use it as a promotional tool in a TV spot? Nothing seems to have filtered through.

The long and the short of it is that Matariki and Predicament are similar in that they have a consensual, almost polite feeling about them, especially the latter. They don't seem to be driven by a central artistic vision - a tall poppy, if you will - and this is not entirely the relatively young directors' faults.

Put in another way, it looks as if those films' producers were administering epidurals instead of delivering those babies bloody, screaming and healthy on to our screens.

Neil Sonnekus

Thursday, November 25, 2010

Comedy by Committee

Architect Peter Highman (Downey Jr) has just crossed paths with Ethan Tremblay (Zach Galafianakis) and his dog at an airport in Dallas, Texas. The latter has caused the former to be shot by a rubber bullet within the first 10 minutes of the movie, but fate and necessity have supposedly thrown them together, for Peter has to get to his wife in Los Angeles, who's about to have their baby. Ethan has to be at a meeting with an agent on the same day, same city.

All good and well. But aspiring actor Ethan has his father's ashes in a coffee tin and rather movingly convinces us that this was a very important person in his life. Yet, when Peter tells how his father asked him to wake him early one morning so that the old man could leave Peter and his mother, forever, Ethan starts laughing. It's a long and forced laugh and no one thought about cutting it.

It's a deeply false note in a movie whose trailer is a comic gem, whereas the real thing becomes tiresome in the extreme. Soon Peter will have a broken arm from a crash (Ethan falls asleep while driving), then he'll survive another crash in a mobile prison caravan that rolls head-over-end (Ethan again) at high speed because he's supposedly relaxed from pain killers, then he'll accidentally get shot in the leg (ditto) and hobble into hospital hours later, but will the child be his and blah blah blah.

The writers (four of them, including the director) of this mess clearly ran out of ideas and resorted to the old trick of inserting a car chase, though it's not featured in the trailer.

Then there is the little question of Ethan's sexuality. It seems like the committee wanted him to be gay - the pink hair brush in the back pocket, the half mincing walk, the ugly but cute pooch - but that it would never become an "issue" between him and Peter. So just avoid him talking about any significant other at all. He's just a camp, absentminded actor who happens to smoke pot for his glaucoma. Talking of which, Downey Jr is pretty camp when the movie starts too.

So there you have it. You can see Due Date in any small town in most countries across the globe, but I prefer the bit of footage I shot on my cellphone while getting drunk in Whakatane. What those good people say is much more funny and real than anything in the movie - and they made me feel welcome in their town and my new country.

Neil Sonnekus

* If you want to see a really good buddy movie try Martin Brest's 1988 Midnight Run with Robert De Niro and Charles Grodin.

Thursday, November 18, 2010

The Medium is the Message

The hammer clearly denoted the communist one and the flag presumably represented evil capitalism. But it was a very hi-tech image and I couldn't help wondering why the world's second-most-vitriolic anti-Americans (the first obviously being radical Muslims) always happily employ American technology and/or actually live in the big Satan. They don't go and work in, say, Minsk, Chengdu or Douala and start a workers' revolt from there.

Seeing The Social Network will no doubt fuel their anti-capitalism because it doesn't paint a very flattering portrait of how the latest social revolution came about, one in which you are free to mention your sore nose or share the latest brilliant idea.

Students of Screenwriting 101 will also be delighted to point out that the film starts with a big no-no: a very long conversation. Ah, but the lecturer might reply, it's because David Fincher (Seven, Fight Club) is directing: he can get away with it. Which is probably true.

His film also doesn't really have a protagonist. Instead its focus is on the founder of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg), the youngest billionaire on the planet. In that initial conversation he proves himself to be a completely charmless little misogynist. Sharp, but charmless, badly dressed and unattractive. So much so that his girlfriend tells him to get lost and doesn't change her mind when he becomes ultra-rich. Maybe the point is that in the world of business and/or IT there are only absentee protagonists.

Almost half of the film consists of lawsuits being conducted against Zuckerberg, surrounded by men and women in stiff grey suits according to their sex, while he maintains his shapeless jeans and those hideous single-strap plastic sandals sports people used to (or maybe still) wear.

What was his crime? Well, according to the film it's a bit of a grey area. It's not like he stole anyone's idea directly. Yes, there already was an electronic network connecting students on campus, but it wasn't being used to decide who's the hottest girl around, or which animal she resembles. For that, Mr Zuckerberg had the brains to write the program exclusively.

So, not a nice piece of work, our Mr Zuckerberg, about whose background we learn absolutely zip.

But every Bill Gates needs a couple of co-founders who will become faceless co-billionaires. Enter Sean Parker, the founder of the failed Napster and, according to the film, a real little shit. Justin Timberlake has become surprisingly adept at playing these morally vacant characters, but according to Vanity Fair the person he portrays so well is not such a turd.

Sure, he likes to party hard - and Fincher is a master at making that kind of American decadence look extremely attractive - but he knows how to sell and realise an idea and, according to the real Parker, "it's technology, not business or government, that's the driving force behind large-scale societal shifts".

What he neglects to say is that nothing just pops up of out nowhere and changes the world, but he doesn't come across as the spineless little slimeball that we see in the movie either. What he has, of course, is exactly what Zuckerberg doesn't, namely social skills, charm.

But if the real Parker is not being portrayed accurately, why should we believe that Zuckerberg is? What exactly would screenwriting heavyweight Aaron Sorkin (West Wing) and Fincher be trying to say? Obviously the film wasn't made without covering all legal loopholes, which Zuckerberg seems pretty good at finding, so what does this story boil down to in the end? A bit of business history, perhaps, a little mythmaking? Maybe not.

Someone playing the aforementioned Gates is featured in a cameo and we all know that the richest man in the world, along with the second richest, Warren Buffett, is giving away the equivalent of small countries' GDP to causes such as the eradication of polio and malaria, and the fight against HIV/Aids.

Judging by this film, one wouldn't be surprised if Zuckerberg were to sell all our personal details to the CIA or whoever else wants to watch us and has enough money, like those Chinese securocrats who think they're fighting a winning battle against a technology - and therefore consciousness - that renders them positively dinosaurian.

But at least The Social Network isn't one of those nauseating college romances, and maybe Fincher used the oldest trick in the cinematic book to convince Zuckerberg, whether face to face or not, that this film needed to be made.

Maybe he, like Parker, appealed to the young billionaire's desperate need for social acceptance, and this time round they both won, since the film is making a killing at the box office.

Neil Sonnekus

A Passage in India

Jaipur, Rajasthan's capital, is not the place to go to if you want to catch a glimpse of India's headlong rush into modernity. A fixture on the tourist circuit, it is best known for its pink-walled old city, its 18th-century forts, its traditional jewellery and technicolour textiles. But for a few days each January, the city provides a conduit to the people and debates at the very heart of contemporary literature.

Set in the grounds of a beautiful heritage property, Diggi Palace, the DSC Jaipur Literature Festival has grown rapidly in the past six years from a small, regional affair to one of international stature that has attracted the likes of Salman Rushdie and Ian McEwan.

Last year, it attracted more than 20 000 people and more than 200 speakers. The five days of reading and panel discussions have become an increasingly important stop for writers looking to showcase their work, and for agents and publishers on the lookout for the Next Big Thing.

Crucially, though, it maintains its local feel. As anyone who has been to Hay knows, the problem with the major lit festivals is that they are usually just a vehicle to sell books and the closest they get to any excitement is when the author fluffs his lines while reading an extract from his latest work.

There's often a sense of "we must pull in the celebrities at any price" - as when Hay spent $168 000 to have Bill Clinton speak in 2001. By contrast, Jaipur has remained largely non-commercial. No one is paid a fee and, more to the point, the entire festival is free to attend. Instead of relying on ticket sales, the fest has managed to shame or cajole institutions like Merrill Lynch into becoming major sponsors, along with the usual suspects like the British Council.

To cap it off, excellent Indian cuisine is served to thousands of participants free of charge and superb live music is performed into the small hours every night. Authors mingle informally with the public too, while there is plenty of networking.

Jaipur is directed by the respected author William Dalrymple, and this January he's managed to attract Orhan Pamuk, JM Coetzee, Kiran Desai, Richard Ford, Anthony Beever, Jay McInerney, Mohsin Hamid, Monica Ali, Jung Chang, Fatima Bhutto, Candace Bushnell and Germaine Greer - to name only a few - to Diggi Palace, along with book lovers from all over Asia and abroad.

It's definitely worth checking out, not least to see whether Tina Brown was right when she called it "the greatest literary show on earth".

Melissa de Villiers

* The Jaipur Literature Festival runs from 21 - 25 January 2011. For more details, go to: http://jaipurliteraturefestival.org/

Sunday, November 7, 2010

A Singular Man

The only other picture in that room I can recall is a photograph of his wife. She wanted to go to the Alps before they grew too old, but she became ill in Austria and was only going to go to one hospital and that was the Rosebank Clinic back in the City of Gold. After her operation the doctor made his inspection and angrily asked one of the nurses where the old lady's drip was.

Up the ill Mrs Fisher piped and said: "He's sitting right here."

How did I come to hear this story? Mr Fisher told it me, smiling fondly. So I can understand that a sweet old man like that might sit down in his chair one night, only a few months after his beloved partner had died, and simply expire due to a lack of interest, missing his beautiful wife, his heart breaking.

But I find it a bit difficult to process that a good-looking man in his mid-50s - and a professor of literature, to further tenuously link the above story - will decide to do himself in because his partner has died. Does it matter that he's gay? Well, this is one of the questions Tom Ford's adaptation of the Christopher Isherwood novel, A Single Man, asks.

Colin Firth's George describes his intention as somewhat "melodramatic", but he's going to proceed to blow his head off anyway, and he does so with all the obsessive attention to detail that probably made Ford one of the top fashion designers in the world. (Talent, of course, helps too.) A pathologist might have told the director that the barrel should aim at the brain, not the spine, but that's a minor detail.

Obviously we sit there wondering when George is going to do himself in, which adds a kind of languid tension to the whole affair.

More importantly, is Ford saying that gays are melodramatic? Maybe just a little, and then there's enough self-deprecation to balance it out with statements like "I'm English, we like to be wet and cold." But, as George says, he doesn't want to live in a world "without sentiment". Not sentimentality, mind, sentiment. There's a difference.

Who does George run to when he hears the terrible news of his lover's death in a car accident? He runs to Charley, played by a slightly heavier-than-usual Julianne Moore. It's a very beautiful scene. There is lovely music (by Abel Korzeniowski), there is rain, there is no speech and there is grief.

But she is his ex, even sexually. And, like so many fag hags, she is still secretly in love with him, still hoping he's going to turn straight so that they can have a "real" relationship, she later confesses - high on gin, wealth and indolence. Naturally it's a statement that infuriates him, but they are friends and he forgives her.

At worst, it seems like the film is aimed very much at a straight market, or at best wants to include it, for the many shots of a floating naked man never show what Keith Richards calls his todger, and even the poster suggests that this could be a film about the relationship between George and Charley. That really is secondary.

Moore's performance of a brash, superficial woman is spot-on and halfway towards what she should have been in Savage Grace. But where are his gay friends? He doesn't seem to have any, and this is not a criticism. One of the important things the film seems to be saying is that George might as well have been married and settled down in suburbia with his loving partner, Jim, played warmly and convincingly by Matthew Goode.

All they really wanted to do was live happily ever after. The only difference is that he's gay and can't stomach the straight neighbours' son, a little corporate soldier in the making. Yet he likes the little girl and so a portrait of a type starts emerging. He likes women, as long as he doesn't have to sleep with them, and he loathes the kind of straight men corporate America was breeding after the war. Fair enough.

And then there is a very telling scene where he walks with an admiring student and watches a man play tennis. There are the usual slow-motion close-ups on pecs and abdomen, but he's still a grieving man. He's not interested in sex right now, but he can still look, which is beyond straight or gay. It's just plain masculine. It's also incredibly gauche.

As for the suicide scene, it's one of the drollest bits of humour seen on film in a long time. George is so busy fussing about things - this feels like Ford the obsessive compulsive going on about details again - that he, well, see it for yourself.

There's even a bit of toilet humour when he literally sits on one, still wearing his tie, watching the neighbours.

Should a straight man play a gay man? There is a camp (pun only half intended) that says it's a no-no and they have a point, much like we don't expect to see a white man playing Othello anymore. But an interesting thing happens with Firth. He is one of the most "natural" actors around, yet here he seems fraught with contradictions, tension; even his gait seems awkward, contrived. It's either a happy accident or a very clever bit of casting.

But what the film does manage to achieve, after all the artifice, is something quite touching. It manages to surpass its own "gayness", its own neuroses, melodramas and deprecations, and boil down to a grieving man (this is not giving the plot away entirely) who can finally give up his sentimentality without forfeiting his sentiment.

In short, it's a moving portrait of a man whose mildness, in the final analysis, is very different to that of the kind and late Mr Fisher.

Neil Sonnekus

* Next week, The Social Network

Thursday, November 4, 2010

The Real Slap's Still in the Closet

I wanted to like this book. I really did. It sounded so intriguing. Reviewers either adored it or hated it - there seemed not to be a moderate reaction among them.

I wanted to like this book. I really did. It sounded so intriguing. Reviewers either adored it or hated it - there seemed not to be a moderate reaction among them.And then there were the prizes. Not only did the novel win Christos Tsiolkas the Commonwealth Writers' Award for Best Novel 2009, it made the Booker longlist this year as well.

Stephen Romei, editor of The Australian Literary Review, called it "a rare quadrella in publishing: a page turner that sells a lot of copies, gets great reviews and then wins literary awards".

So where did we go wrong, The Slap and I?

Okay, there's a dynamite narrative hook at the start - the slapping of a brattish four-year-old (who is still being breastfed, incidentally) at a barbecue in suburban Melbourne.

Within a day the parents of the slapped child have the slapper arrested. But then the plot broadens, spooling out over nearly 500 pages in its ambitious attempt to lay out modern, liberal, multicultural Australia across the rack.

Several factors traduce the book's ambitions. There's the soap structure, for starters; with each chapter, Tsiolkas shifts his point of view to a different character who was present at the barbecue - a Greek immigrant in his 70s, an ex-hippy-turned-suburban-mum, an adolescent girl in the first flush of love, an Aboriginal convert to Islam.

Most of these characters are unpleasant in a wide variety of ways, but that's not the problem - they're cardboard cutouts that talk in cliches. Although suburban violence and anger is one of the book's key themes, everyone seems to get angry in exactly the same tone, even in the same words. Perhaps this is Tsiolkas's point, but the repetition means he doesn't make it very effectively.

Characters are constantly describing how they long to smash their fists "into the face staring back at him" or to smash the kid against the wall", or "to smash a cricket bat...once, twice, a hundred times into the little fucker's head, made him pulp and blood."

Or, just for variation: "Harry did not take his eyes off the cunt. If he could only smash his fists into her pretty face."

Then there are the sex scenes, which are cringe-making. This is porn sex, really, a seemingly endless loop of thrusting cocks, grateful cunts, moans and groans. No matter how hardcore the experience, Tsiolkas's women lap it up - after one particularly relentless session the man apologises to his wife and she meekly replies, "but I like making love to you."

Tsiolkas, who is gay, told an interviewer from the London Times that he relied on advice for these scenes from three women writer friends, one of whom read an early draft and told him: "The women are orgasming like men. Women don't come that quickly. Dial it back."

Blimey. So this is the dialled-back version.

And the prose is too often clunky. On holiday in Indonesia, one character is struck by the "gentle smiles" of the locals, the "cheer and fearlessness of the children". Or: "She did not look her age but looked fantastic."

Somewhere within The Slap there's a thoughtful state-of-the-nation novel trying to get out, one that highlights the casual racism that lurks within Australian culture; the tensions within an uneasily assimilated multicultural society; the contradictions of liberalism.

But the quality of the writing too often lets it down. And, although Tsiolkas assembles a diverse cast, what he doesn't do is make their ethnicity or class count for very much, or investigate in any detail these different worlds.

He's good at plot twists and turns, and that's what kept me reading until the end - on that level, the book delivers the same kind of satisfaction one gets from a well-crafted airport thriller. But "a tour de force...a novel of immense power and scope"? (Colm Toibin)

Slap me and wake me up. I must be dreaming.

Melissa de Villiers

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

Peace Be Upon You

That the object of his desire was a Muslim woman was telling. His character had in fact been seduced by the Middle East, for all its complexities, which is a far cry from the usual American denial of showing how "our" boys are suffering in one of those wars instead of asking why they're actually there in the first place.

Films like The Hurt Locker.

In fact, a salient but understated point Scott makes is that the Middle East has an erotic charge about it, and it's worth investigating that, along with all the other geopolitical considerations.

Once people start falling in love across races, cultures and religions life becomes infinitely more interesting - and complex. On a micro-scale, you can't get more political than getting married.

But in the two films under discussion today there is no love lost, let alone glimpsed or even desired. In the first, A Prophet, which won the Grand Prize of the Jury at Cannes, a Bafta, the Golden Globe and has been rightly nominated for a foreign Oscar, there is a warning, a cautionary.

What makes it so powerful is that Malik (Tahar Rahim) is a nonentity when Jacques Audiard's film begins. The only thing that distinguishes him from other French people is that he speaks Arabic, but he comes from the streets. He has no parents, no political or religions affiliations.

But the first criminal and symbolic act he has to perform for the Corsican mob inside is kill an Arab - who might snitch on them - to ensure his own safety. This is virtually the only time we see him feeling anything, not because the man is an Arab, but because Malik is not a killer. So he does what has to be done, but then that man comes to "visit" him thereafter, to guide him, mentor him, praising God.

Though a very long movie, the shift from Malik's complete subservience to utter power in six years is almost imperceptible, his face showing very little again.

And if the implicitly Catholic mob, as represented by Niels Arestrup's obscenely brilliant prison don, are always violent towards Malik, then the Muslims offer him something that is central to their faith. Family. And I don't mean the family of man, or men, I mean his friend is dying of cancer and offers Malik his beautiful wife and child. What street urchin would say no?

So if ever there was an allegory on how Islam became radicalised, this is it. It's very scary, and very necessary.

On completely the other end of the scale is Chris Morris's scathing satire Four Lions. Note, it is not a comedy, it is a satire, which means it is there to highlight the absurdities of something. In this case it is a quartet of blithering, fundamentalist Muslims idiots with Sheffield accents.

Using all the techniques of farce and slapstick, Morris sends up some of their more ridiculous ideas, often using news-like camera zooms.

On a domestic level, when the imam comes to visit the leader of the revolutionaries, Waj (Kayvan Novak), he has to shield his eyes from seeing Waj's (very beautiful) wife, Sophia (Preeya Kalidas). The scene ends up in a suburban water-pistol fight between the married couple and their imam because he finds it repulsive to be in the same room as a woman, but otherwise he's a peaceful sort who doesn't intend blowing people up.

Sophia, however, discusses her husband's martyrdom as if they're planning a Sunday morning picnic.

Extremism takes a knock, literally, when Barry (Nigel Lindsay) suggests they should blow up a mosque so that they can radicalise and mobilise more Muslims. Waj says that is akin to hitting yourself and finally persuades Barry to do just that, giving himself a blood nose.

But always there is the reality that bombs are bombs and they can completely spoil your day and, even though Morris only half covers himself from a fatwa by showing just how stupidly dogmatic the English are as well, one wonders what Muslims would think of this film. Would they laugh as much as Westerners? It would be interesting.

On a purely formal level, this outrageous flick starts losing steam towards the end, but it has more laughs in it than most Hollywood comedies put together anyway.

And then there is the question of who has the last word. The satirist or the historian? It is quite conceivable that the latter might one day come to the disturbing conclusion that the man who almost single-handedly dragged Islam into the spotlit glare of global scrutiny, George W Bush, was also a blithering, fundamentalist idiot.

Neil Sonnekus

Friday, October 15, 2010

Going to Town

Furthermore, he had a fine understanding of how menace works, and he was competing against another contemporaneous masterpiece of menace set in Boston: Martin Scorsese's Oscar-winning The Departed.

All of that skill is still apparent in The Town, but it's kind of watered down.

This could be because he is rather self-consciously hauling his own, rather awkward tall frame through the lens, but he is still pulling those performances from others - notably Rebecca Hall as Claire, Blake Lively as a hard-done-by Krista and Jeremy Renner, fresh from his acclaimed showing in The Hurt Locker, as her brother, James.

Anyway, the titular town is Charlestown, a Boston suburb which apparently produces the most bank robbers anywhere. So it is not a very upmarket kind of place, yet Affleck (pardon the pun) goes to town with expensive aerial shots of the city and the titular suburb.

It may be a small point, but it's wrong. These people don't see life from above, they see it from down below, like Scorsese's characters. They're too busy in their cesspool of survival to have a bird, God or Trump's eye view of the whole affair.

Those are the negatives, bar one.

On the positive side there is the rather engaging relationship between Doug (Affleck) and Claire, a bank manager who is briefly taken hostage by him during a robbery (he's behind a skeleton mask) but treated humanely.

If his effort to engage her afterwards is somewhat contrived, then one does get a sense of the tentativeness of a new affair. Initially, of course, he only wants to know whether she saw anything identifiable about the thieves, since she's been questioned by the cops.

The only thing she saw of the robbers was one of their tattoos, belonging to the always dangerous James, on the back of his neck. So along he comes, in broad daylight, and joins them at an open air restaurant, the tattoo quite visible.

It's masterly. Will she she see it or not? Has he been spying on his virtual blood brother or not?

Doug's history is economically referred to and made integral to the story, and the fact that the kingpin of these parts fronts as a florist, played by the prunish Pete Postlethwaite, is another excellent touch.

Moreover, Affleck the director has a wonderfully realistic streak to him in that some of his characters actually get hit in the crossfire; if someone gets smacked over the head with a rifle's butt they actually bleed; if Jon Hamm's FBI Agent Frawley blasts a getaway car's tyres with a shotgun they actually burst.

How refreshing.

So this is not the worst or most most mediocre heist film you'll ever see, far from it, but there is a danger that it could become a cult movie in the distant future for all the wrong reasons.

A bunch of aliens might worship its hidden message that, forsooth, we only see Affleck and new "it" actor Hamm every third day of this story, for both of them sport such a designer stubble virtually all the time, and that just ain't real.

Neil Sonnekus

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

Soul Food

But then Soul Kitchen goes a step further and turns out to be a romantic comedy. Could this be possible? Could it possibly work? Well, yes, actually. Rather well. And the reason why it works might well be the same as why the German national football team is so much more interesting these days.

That is, it no longer consists of only Schweinsteigers, Schillers and Schumachers. Not only are there a couple of Polish names in there now, but also quite a few Turkish ones, even an African. In other words, the team is no longer purely European. The old gene pool is being given a shake-up.

Hamburg-based director Fatih Akin is of Turkish extraction - his parents were probably so-called guest labourers (Gastarbeiter) - and his leading actor and fellow scriptwriter is clearly not echt Deutsch with a Greek name like Adam Bousdoukos.

So the latter as Zinos Kazantsakis has a restaurant that sells bad food to appreciative people. The only problem is that he has a brother, Illias, who's a criminal, played by Moritz Bleibtreu, who always has that air of Fassbinderian decadence and intelligence about him.

Zinos also has a purely Aryan girlfriend, Pheline Roggan, who is as precious (but okay) as the day is long; and he has an elderly tenant, Sokrates (Demir Gokgol), who verbally abuses him and never pays the rent. Such is life.

Everything seems to go wrong when Zinos slips a disc in his back and spends the rest of the movie walking like, as Illias says about someone else, he has a carrot up his arse. It's very funny because Zinos just happens to look a lot like Jim Morrison of The Doors - in other words, a god.

That is about the only thing the title of the movie and the song by that band has in common, nor does it really deliver on its promise of being a soul music-themed movie. It's way too inclusive for that. There's everything from the stuff you'll hear in elevators to the beats you'll get in an Istanbul disco.

And just to add to the tasty stew, there is Zinos's precious chef. Birol Unel as Shayn Weiss is every millilitre the kitchen dictator, stylish fringe, camp rage and all; and who wouldn't fall for Zinos's Turkish physio, Anna (Dorka Gryllus)?

If the film is predictable in its romance and plot - Aryan property developer wants to take over by means foul - and if the device as to how Zinos wins back his restaurant after brother Illias gambles it away is utterly contrived, then it scores in the areas that count.

That is, not only is it a celebration of the new world citizen, the migrant; it is also a reminder that some of us are - or once were - young, wild, beautiful and divinely cuckoo.

Neil Sonnekus

Thursday, October 7, 2010

The Finkler Question

Even the briefest glance at Howard Jacobson's face would seem to explain why these are the words often used to describe his work (the other one is "funny"). Surely those craggy, prophet-like features must never be more than a twitch away from a thunderous scowl? Journalist Allison Pearson once described him as looking like "God after a bad day at the book

makers", and there's definitely something there that suggests grumpiness on an epic scale.

makers", and there's definitely something there that suggests grumpiness on an epic scale.Luckily, Jacobson turns out to be an interviewer's delight - easy-going, open and brimful of bonhomie. This sunniness is at least partly a consequence of his latest novel, The Finkler Question, reaching the shortlist for the prestigious Man Booker Prize.

Literary gongs have been a bit of a sore point with him until now, even though his books get glowing reviews (Jonathan Safran Foer called him "a great, great writer") and he is often compared to Philip Roth. Yet come the awards ceremonies...nada.

"I've had this reputation as a good writer who is constantly overlooked, and I've been quite fed up with it," he tells me. "If you're identified with a certain kind of non-achievement, it counts against you in the end. So now I feel that particular spell has been broken, and I'm pleased about that."

Of course, there is no accounting for judges' tastes. But there is always the possibility that his novels trade in subjects still off-limits to some, like humour and the Holocaust - the main conceit behind Kalooki Nights (2006). Or perhaps it's because they deal with other issues that cut uncomfortably close to the bone, like British anti-Semitism.

"My father always said: 'Keep your head down, stay schtum.' In the UK, you must demonstrate your remove from Jewishness if you want to feel more English. That's not the case in America, where you often get the feeling that Jewish life is almost synonymous with general cultural life. But over here, while we're not disrespected or disregarded, the Jewish way of thinking and speaking has simply not shaped the culture in the same way and probably never will."

That aside, there is no doubt The Finkler Question is a triumph - funny, clever, and dark. Its protagonist, Julian Treslove, is a typical Jacobson creation: a middle-aged man much given to angst, falling heavily in love and regarding his male friends as rivals. He's also been the victim of an anti-Semitic attack. Or so he thinks. The problem is, he's not actually Jewish, though his two best friends are - Sam Finkler, philosopher and author, and Libor Secvik, his former teacher.

Sam and Libor are both newly widowed, and Julian's feeling left out - while the other two debate Zionism and mourn their wives, all he's got is an uninspiring job as a celebrity lookalike and a brace of sons he doesn't care to remember. So he decides to learn Hebrew, studies Jewish history, meets a Jewish woman and gets a job in a Jewish museum. But can all this satisfy the need to belong?

This is Jacobson's eleventh novel and, like all its predecessors, it uses humour to drive home his discursive, digressive but always thoughtful interrogations of what it means to be a Jew in England.

"I have always argued for the primacy of comedy in fiction. I don't mean jokes - I mean the illumination of another way of seeing, the sudden turning of an action on its head; not to make light of it but to enrich it."

Such as his depiction of one particularly woebegone character who keeps a blog recording his attempts to regrow a foreskin. Or the bitingly satirical scenes where Finkler spearheads a group called "Ashamed Jews", whose raison d'etre is their grievance towards Israel.

Jacobson's speaking to me from his converted loft in London's Soho, which he shares with his third wife, television producer Jenny de Yong. It's a seemingly natural habitat for a sophisticated, successful author - yet his roots are in working-class, Jewish Manchester. His late father was a "market trading, taxi-driving magician", his mother raised their children at home.

"We were Jewish in a very secular way. We were expected to have bar mitzvas, but we didn't know what it was, really. Our parents got a bit upset when we went out with non-Jewish girls - there was a feeling that you weren't meant to 'marry out'. There was no sense of the kind of Orthodoxy that is in the air at the moment."

Both his parents had an abiding love for culture: his father for opera, his mother for books, and that led Jacobson to pursue a degree at Cambridge. He later taught literature at various universities, but says that his academic career ran aground in the late Seventies. "I neglected it because I wanted to be a writer. I didn't do all the things you were supposed to do."

Yet his literary career took a while to get going. His first novel, Coming From Behind - often described as a Jewish Lucky Jim - was not published until 1983, when he was in his 40s. Once he'd got over the fact that he was no Tolstoy, he finally found his voice.

After that, all he wanted was success as a writer and it still matters to him more than anything, even though he's busier than ever. He's about to publish a collection of the columns he writes for The Independent, he's just made a film about British art for Channel Four, and he's also well into his next novel.

And, of course, there's the upcoming Man Booker. How does he stand the anticipation?

"My mother, who is in her late 80s and pessimistic - Jewishly pessimistic - gave me a piece of her mind on that. 'Don't hope for much. Enjoy it now! Let this be enough.' It's good advice, actually, because right now I do feel blessed."

Melissa de Villiers

Monday, September 27, 2010

Touched by the Moon

Mike Riddell is the writer of the Kiwi film The Insatiable Moon and his wife, Rosemary, is the director. Mike is an ex-Baptist minister and Rosemary is a judge.

I was meant to speak to both of them but blew it and ended up having a rambling chat with Mike in a coffee bar in Ponsonby, where the film is set.

Unlike most Kiwis Mike doesn't say "yeah" and, more like a Zen-Buddhist than a Baptist minister, he tends towards cheerfulness.

NS: According to Wikipedia...(laughter)...you're a bit of a hippie.

MR: Ja, absolutely. I was part of the movement and sort of ended up following the drug trail all around the world and ended up in prison in Morocco.

NS: Wikipedia just says you travelled in North Africa... [raucous laughter] Is this what possibly led to some sort of spirituality?

MR: It's hard to know that. But I remember walking around the prison yard for a couple of hours a day and thinking about the meaning of life and all that sort of stuff. I was a real acid head, used a lot of LSD. I guess that was all part of the spiritual quest for me...

NS: And the hat?

MR: Partly because if I lift it I'm bald [cheerful laughter], but also partly it's a sort of a mark of identity. I'm just a hat person. For years I've had a huge collection of hats.

NS: How did you and Rosemary meet?

MR: We met in a flat in London in 1973/74 or something like that. We've been together for a long time. We've got three kids. Got married in 1975.

NS: Was she a lawyer then?

MR: No, we did all kinds of things. She started off doing home help stuff with aged people [a waitress brings him a cup of hot chocolate with two marshmallows]...nice stuff...but before she met me she'd been doing some professional acting stuff. She worked for TVNZ. And she kind of went to the UK to extend her acting career, but found it really tough over there. Then we had three children together, so it wasn't until later that she went to university and tried studying and she got really good results, so she tried law, became a lawyer, shifted to Dunedin, and became a partner in a law firm.

NS: Now she's a very talented director.

MR: [laughs] But the creative stuff has followed all the way through.

NS: Are you still based in Dunedin?

MR: No, we had to move to the Waikato. It's very difficult to be a judge in the town where you were in a law firm. We would never have moved from Dunedin otherwise. So we live in Cambridge now, on the outskirts of Hamilton.

NS: What's the title of the film all about?

MR: Well, it's the same as the book. In the book the moon plays a bigger role than it does in the film. It's much more prevalent. It's about the pulling power of the moon, not only with the tides but with human lives, particularly people's mental health and wellbeing.

NS: Hence lunacy.

MR: Ja, exactly. So it's about this moon that's constantly shifting people's lives around.

NS: Were all the moons in the film real?

MR: No, the big full moon was CGI. We spent a couple of nights trying to get it, but we couldn't.

NS: You mentioned that Rawiri [Paratene] insisted on playing the lead role?

MR: He claimed the role, ja. He read the novel while he was filming Whale Rider and wrote me a letter saying it would make a great film and he'd like to write the screenplay. So I said, "Well, I've already started on the screenplay. So he said, "All right, then I'm playing Arthur. No one else is playing Arthur." That was in 2002.

NS: The rest seemed to flow with that same kind of personal involvement.

MR: Ja, relationships have been at the heart of the film. Both the UK producer and I have always had a concern that the making of the film had to be in keeping with the story. It was always important to us.

NS: Just to go back a bit, did you become a Baptist minister after you and Rosemary got back from the UK?

MR: Ja, it was quite convoluted, really. I kind of drifted into Christianity with a bunch of hippie/druggie people. Then I wanted to do more studies. So I ended up going to the Baptist Theological College here in Auckland. But I got to the end of that and still had a lot of questions, so we went to Switzerland for two and a half years, where I did a postgraduate in theology, came back here for eight or nine years and was the minister of the Ponsonby Baptist Church.

NS: Which is where you met this Arthur character?

MR: Ja, that's right.

NS: I still find it quite a jump going from what you call an acid head to a Baptist minister...

MR: Ja, it was really...

NS: You didn't go the Timothy Leary or Allan Watts route.

MR: It could have easily [gone that way]...I've always been interested in all sorts of religious streaks. There was a strong Buddhist phase that I had...I mean, there were all sorts of influences, but as much as anything I think it depends on context and circumstances and where you happen to find yourself. But I was very much a fish out of water in the Baptist church.

NS: I would imagine so. [even more raucous laughter]

MR: The only way I survived was that the Ponsonby church gave me a very liberal hand...

NS: Has Ponsonby always been considered a "progressive" area?

MR: It was a slum, really. Freeman's Bay and Ponsonby were slums.

NS: Oh, when?

MR: Right up to the Sixties. It started off as working cottages...Irish immigrants...It was a bit of a Catholic area. Then it got gradually run down, lots of students, lots of psychiatric patients from Carrington, and then Pacific Islanders came and settled here. So it wasn't until the Eighties that it started changing.

NS: Now those cottages are worth a fortune.

MR: Exactly. In the novel, there's a lot about the changing nature of Ponsonby, its history.

NS: Back to the Christian theme, the film can't exactly be described as Christian. [yet more raucous laughter]

MR: Absolutely. We don't consider it a Christian film, as such, even though it's informed by a lot of Christian themes. We think it's a spiritual film and it appeals to people with a spiritual bent... It's funny, we showed it to a bunch of distributors in the UK and an American said we should edit the film so that it would suit the Bible belt, so we said we want all those Midwest Christians protesting outside the cinema! [laughter] That'll sell tickets for us.

NS: What is the law about mental patients?

MR: The boarding houses are run as a private operation. The manager owns them. But the patients get extra money according to their disability and that's how the manager makes a profit.

NS: But you do still have asylums?

MR: No, there's only respite. there are a few forensic wards if you are criminally insane, and there's compulsory treatment for very serious cases, but they are constantly under review and anytime a patient says "I want to get out," there has to be a hearing. But by and large the model is they've closed asylums down. There's now a model of so-called community care.

NS: The problem with that model is the paedophile in the story...

MR: Absolutely. We wanted to confront that problem head-on. That's the most controversial part of the film. It does kind of bring it out into the open, doesn't it? Instead of hiding it, allowing it to fester...

NS: You guys played with the idea of Margaret being pregnant?

MR: It was entirely intentional that it should remain ambiguous. We wanted it to be one of the things people might talk about afterwards. [We did]. There were all kinds of levels of ambiguity [and delicious contradictions]. Is Arthur insane or is he someone special? The book was a little more pushy about those issues.

NS: At one stage Margaret says there's an incredible gulf between them. She doesn't just mean as far as mental health is concerned. She also means culturally. She's a pakeha, he's a Maori.

MR: I've always been a believer in the local being the universal.

NS: Were you aware of the danger that you're using friends' money?

MR: That's what I thought was most risky; we knew all the people who'd invested. It's a huge responsibility.

NS: I constantly read about films being made here independently, but we never hear about 90% of them afterwards...

MR: I was aware of that all the way through. You try to spell it out for people, but they don't always understand what the risks are.

NS: Had you and Rosemary worked on anything else together?

MR: Ja, I produced her [award-winning] short and we also did a play together.

NS: Is there any reason why the New Zealand Film Commission hasn't put any money into the film?

MR: To be honest, I've never quite understood...All I know is they never resonated with the script early on, and from that point on they felt they needed to defend their point of view, even when we were getting very positive reactions to the script from other quarters, overseas. Ja, in many ways I think they've backed themselves into a corner. I don't think they ever thought there was a feature film in there. The astonishing thing to me is that they have seen the finished product and they still don't like it. They still think it is a film that won't travel...Our central values have always been story and performance. We were forced to shoot on 2K [as opposed to 4K] cameras, but audiences in my experience will forgive an awful lot of they're caught up in the story.

NS: Like that wonderful Oz film, The Castle, which was shot in 11 days.

MR: That's exactly right. Kelly Rogers, the head of Rialto distribution, says he sees it [The Insatiable Moon] as a kind of As It is In Heaven. It just kept on going. It had a life. But I really don't know about the Film Commission. We're still talking to them. What we're trying to say to them is that the more positive reaction we get, the more embarrassing it gets for you. You've got a chance to turn it around and make it positive.

NS: Did they put anything into post-production?

MR: They put $25 000 into post-prod, but that's only because policy says they have to. [laughter]

NS: So what has the reaction to the film been across New Zealand?

MR: Brilliant. We've done Q&A all over the place.

NS: I saw the two of you watched the film with us at the community centre the other night. How many times have you seen it? Aren't you sick of it yet?

MR: I've seen it about 70 or 80 times. I don't know. Rose and I talk about that. We quote it to each other. But we always get drawn into it, which is an encouraging sign. The other thing I enjoy about it is seeing how the audience reacts to it, how different audiences react to different parts.

NS: Where does it go next?

MR: We've got a UK distribution deal. It will release there early January.

NS: And what's next for you?

MR: I'm a kind of writer for hire. Just thrashing out a script for people who need one in a hurry. Then two others for international co-pros. And the guys who played the characters in the boarding house, they're keen to work together again, so we've put an idea up for a TV series.

NS: That's a fantastic idea.

MR: So we'll try to shoot a pilot for that next year.

NS: Can't you just show them the film? Surely it speak for itself?

MR: No. Things are pretty tight.

NS: I couldn't believe that Lee [played by Pete Tuson] was simply acting.

MR: He actually spent some time in South Africa. But he nearly lost the part because he's got a row of sparkling gold teeth, like Oddjob in the Bond movies, so we had to black those out. He's a lovely guy. He often drove all the way from Whangarei for two and a half hours to be on set at 6am.

NS: That's amazing...

MR: Great team of people. And of course Rawiri. He's always on the lookout for people on the margins...when it came to lunchtime he's always the guy at the back of the queue.

NS: I must say his construction of "heaven" in that motel room was very fast.

MR: [laughs loudly] It was, wasn't it! But the script I'm working on now will interest you. It's about the 1981 Springbok tour [that virtually divided New Zealand].

NS: You were one of the protesters there...

MR: Ja, and they want to shoot that by next year.

Neil Sonnekus

* Okay, so I'm publishing a day late. But I had paid work this week, and that was a real shock to the system. Things should return to normal going forward. Also, I see that the Rugby World Cup ad has been shortened and no longer features the Springboks. So you can see just how powerful a simple blog can be...

Thursday, September 23, 2010

Post-Workshop Postponement

I have been on a screenwriter's workshop in Wellington and my head is spinning, so I'm moving the interview I was going to publish today to next Friday. This also takes us closer to the opening date of the relevant film, The Insatiable Moon, which is October 7.

I hope you have a fabulous weekend and week.

Neil Sonnekus

Thursday, September 16, 2010

Read, Pray, Love

* The photograph was taken by Neal Harrison

Once in a Blue Moon

.jpg)

The Insatiable Moon manages to give goodness a whole new slant - and quite a bit more.

Directed by Rosemarie Riddell and scripted by her husband, Mike, from his novel of the same title, this film bristles with a benign intelligence and courage for the simple reason that it does not avoid pain, but embraces it with an entertaining clarity and compassion.

It might be interesting to know that the director is a judge and the writer is an ex-Baptist minister. If the former shows excellent discernment in her casting and direction, then the latter shows perfect restraint from practising his former profession on celluloid, even though the core scene in the film is set powerfully in a church.

Equally interesting is the fact that the film was funded by friends, in the middle of a recession, and they too showed excellent judgment, since they're sure to make their money back. It is not always thus with so-called crowd-funded films. The excellent cast and crew should also be commended for the work they did on this film, often for little money or none.

So what is it all about? A handful of mental patients are kept in a halfway house in Ponsonby by Bob (an excellent Greg Johnson), a man with a mouth like a sewer and a heart of gold. One of his "inmates" is Arthur, who considers himself the second son of God. Some of his reasoning might well bring him into contention for the No 1 spot, but then he has a vision.

Played by Rawiri Paratene, who effectively insisted himself into the part, he brings a Lear-like majesty to this man who intercedes between the living and the dead, the sane and the insane, the criminal and the law-abiding, the artist and the everyman.

In a hilarious interview with a snooty TV journalist, he quite gently shows her up to be the one who needs therapy, not him.

But the previously working-class suburb of Ponsonby has gone upmarket, and people don't want to live next to these strange and deranged people, one of whom is a convicted paedophile. These are understandable fears and the film deals with those fears rather than scorns or, worse, avoids them.

Bob needs money to keep his halfway house going, the estate agents are knocking at the door like the proverbial wolf, and Arthur has done that one thing that could drive any man insane. He has fallen in love with a vision, an ordinary, unhappily married woman, played pitch-perfectly by Sara Wiseman.

Thursday, September 9, 2010

Interview with Suchen Christine Lim

"Free speech" and "the city-state of Singapore" are not phrases that fit together well, despite cautious moves over the last few years to liberalise Singaporean society and widen the space for expression and participation. July 2010, for example, saw an international furore over the case of veteran British journalist Alan Shadrake, who is facing two years in jail for writing a book that criticises Singapore's shameful use of the death penalty.*

I wanted to create a fourth protagonist who was the history of Singapore, and for this to be a "her", not a "he". I wasn't caught up in any kind of feminist debate about this, I just saw Singapore as a woman like my grandmother who, by the way, had bound feet, like the character in my book. Part of the story is based on my grandmother, and her relationship with my grandfather's second wife. The two of them, as they grew older, became very close, and this second wife was the only one entrusted with the duty of washing my grandmother's feet.

What was it like starting out as a writer in a very conservative cultural environment?

It wasn't easy. But I have to take my hat off to writers like Lee Tzu Pheng and Edwin Thumboo, poets who were publishing in English at a time when it was even more difficult: one, because of the political climate; two, because back then people in Singapore were so focused on the economy, on getting ahead, on filling the rice bowl. You were faced with attitude like: "So what's all this airy-fairy, arty-farty stuff like writing, eh? You've no business to write!" I was told to my face: "Sorry, Suchen, we don't read Singapore writers. We'd rather read Jane Austen and George Eliot." Proudly it would be declared to you, the Singaporean writer, that the reading public was only interested in the classics or Nobel prizewinners.

Yes, because we have a confidence now that wasn't there before. There used to be what people called a "cultural cringe" - a lack of confidence in all things Singaporean, coming mainly from people who had been educated in English. That's when I started to consider myself very fortunate to have had uneducated, dialect-speaking grandparents, both great sources of stories, and of cultural confidence too.

I was always conscious, starting out, that I was different, at least from Singapore writers here who are Chinese. I do not write like people in China. I am very clear about that. And so you will see me describing myself as of Chinese ethnicity, but situated in South-east Asia.

Is there a specifically South-east Asian approach to writing fiction?

So I see myself as coming from a tradition that tries to use writing, like the Taoists, to create balance and harmony. If the subject is not balance and harmony, if the work needs to be about chaos, then at least it should lead to some understanding of that chaos. I mean, you know there is good and evil, yes? Yin and yang. So let's deal with it, as honestly as we can, without destroying somebody in order to achieve artistic success.

Well, I suppose it was partly to do with the fact that my family were traders. I grew up thinking I would sell congee [chicken porridge] - there wasn't any sort of encouragement, especially for girls, to pursue a literary career. Becoming a teacher, which I went on to do, was already considered different enough.

What's the most difficult aspect of writing for you?

It's writing that first draft. Incubating a novel and having to sustain it - it's like gardening every day, and waiting for something to grow. Sometimes when you watch the plant, the plant does not grow. And then you've got to turn away and wait - and when you come back it has grown an inch. In a way, you are kind of playing with your mind a hide-and-seek game. (I'm sorry about all the gardening metaphors - you can probably tell that I'm a keen balcony gardener!). So the difficult part is the cultivation of an idea - learning to wait fruitfully, learning to wait productively.

Holding your nerve...

Yes. Because I think all artists are insecure, in a way. The production of a book is the culmination of a journey dealing with insecurity, and learning how to handle it creatively. At time we may even feel depressed, but that's one way of coping. Of course, it took me many years to figure this out. Even up to the time when A Fistful of Colours won a major prize, I still never described myself as a writer. I always just said "I am writing" - using the verb, not the noun. I still felt almost like a fraud.

What's next for you?

I'm writing a novel, but I can't talk about it yet. But I'll always be writing. I can't stop. And I would very much like to believe that writing is an art form in which the older you get, the better you get. One of my mentors is Francisco Sionil Jose, the acclaimed Filipino writer. He's 85, and he has just published a new novel. I remember him saying to me: "Suchen, don't be in a hurry; just write. And go on writing." I've never forgotten that.

More on Suchen at http://suchenchristinelim.com/